Breathe Well Georgia

Project One: What is the effectiveness of a PR programme adapted to the Georgian context compared to usual care for patients with symptomatic COPD of MRC ≥2?

Study design: Cultural adaptation and feasibility RCT

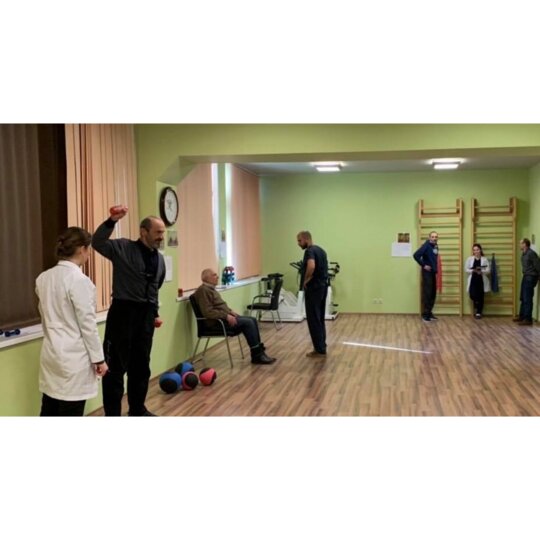

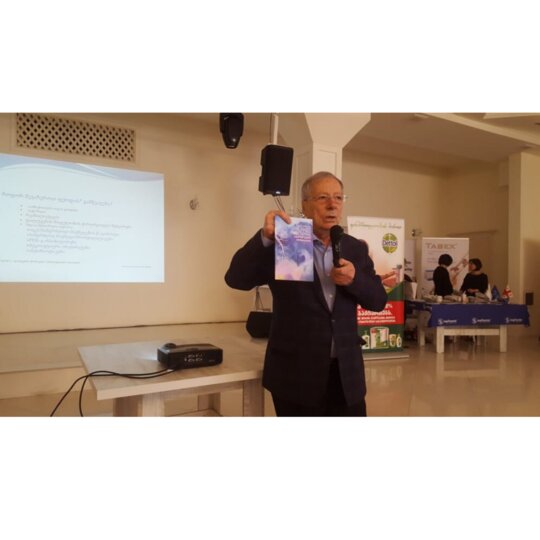

Progress update: The team recruited 60 subjects for their feasibility trial, which was a randomised controlled trial. The trial provided cohorts with an 8 week programme, which entails 16 visits on site, comprising of physical exercises and educational sessions. The trial had high patient follow-up rates. The project also included qualitative interviews with patients and staff. Data collection is finished. The team are in the analysis and write-up phase of this project, with an aim for publication and dissemination of the results in August 2020. The results will be submitted for publication (Spring 2020). Cultural adaption of the study protocol was undertaken and necessary revisions made. Ethical approval for the study has been obtained and it has been registered on ISRTCN.

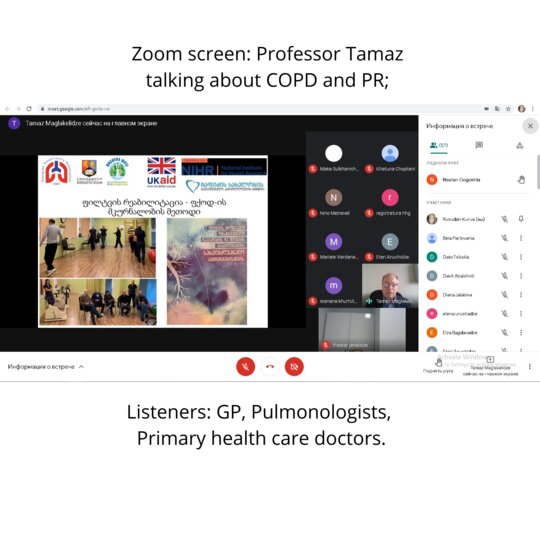

Training of pulmonary rehabilitation specialists was conducted in September 2018. The information materials for the educational sessions were prepared and the required equipment put in place.

Project 2: To explore barriers and enablers in the diagnosis and management of COPD in primary healthcare in Georgia and to identify needs for capacity building of primary care professionals regarding COPD diagnosis, management and treatment in Georgia

Study design: Data collection: One-to-one interviews. Data analysis: Framework analysis. Sample size: n=20 (or until thematic saturation is obtained).

The Population: Primary care doctors in rural and urban settings. Purposive sample with maximal variation of: age, experience, location, respiratory training and size of GP practice.

Progress update: This project has obtained ethics approval and recruitment of GPs has started.

Background

Georgia has a population of 3.7 million (1). Average life expectancy is 73 (2). Georgia gained independence with the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, and inherited its health system model. Health care was given free at the point of care and was centrally organised in a hierarchy from district to state hospitals, all owned and all employed by the state.

In 1994 the system was reformed and introduced health insurance, user fees and a focus on defining the responsibilities and cover of the public health system. The new system was deemed to have failed and was abandoned in 2004. It was replaced by a system covering only vulnerable groups, about a quarter of the population, offering them around 70% discount on care. In 2008 the system was once again reformed and a programme was initiated were private insurance companies provided compulsory insurances regulated by the state. Those unable to pay received vouchers from the state for insurance payments. Out of pocket expenditure still made up the majority of health spending, with a large part being informal payments. Meanwhile the infrastructure was privatised with facilities sold to insurance companies and other private investors, whilst their operation was regulated by the state (3). In 2013 the Georgian government launched a new universal healthcare programme (UHC), and replaced the insurance companies’ plans with a state-owned and state-operated insurance system.

COPD burden and management

Although relatively few women are regular smokers, almost 40% of men are. This contributes to a COPD prevalence of 3,677 per 100,000 (4). The Georgian health system relies heavily on secondary and tertiary care, even as the primary care system is undergoing rapid upscaling. This also applies to COPD care, with a lack of awareness as well as equipment for diagnosis and treatment in primary care centres. Consequently, COPD is mainly handled within secondary care, where spirometry is commonly performed. There are ongoing efforts to increase awareness among primary care workers regarding COPD and tobacco related illness, as part of the Tobacco Control State Program, although coverage is still limited. An over-reliance on secondary care also increases inequalities regarding access, due to the geographical location of hospitals.

References

- Geostat 2016. Statistical Yearbook of Georgia 2016.

- NCDC 2015. Statistical Yearbook 2015.

- Chanturidze, T., Ugulava, T., Durán, A., Ensor, T., & Richardson, E. (2009). Georgia health system review. Health Systems in Transition, 11(8).

- GBD 2016. Global Burden of Disease Study 2016.